The Putin Effect (Stage 1): Financial Markets

Alastair Winter

(Hay una versión en español de este artículo aquí.)

This article focuses on Alastair’s views on global macro allocation strategies. For relevant macro fundamentals background to this article, please see his preceding articles on global macro fundamentals in Timón Económico, The Putin Effect (Stage 1): Geopolitics and The Putin Effect (Stage 1): Macroeconomics.

Financial Markets: at the beginning of the beginning

Investors still seem to be struggling to work out how to deal with the invasion. They did all the ‘right things’ at first: they sold the rouble and hryvnia and local currency bonds. The rouble duly halved in value against the dollar but is now back to pre-invasion levels, as speculators have weighed in. Trading at a ‘mere’ 10%, the 10-year Russian sovereign bond yield has also recovered, after two scary spikes. The punters also sold off Russian equities once the market was re-opened, and the MOEX tumbled by 40% to a bottom from which only about a third has since been recovered. It must be noted that these are no longer free markets, as they are subject to both official interventions aa well as wild speculative flows. It is best not to think about Ukrainian financial instruments!

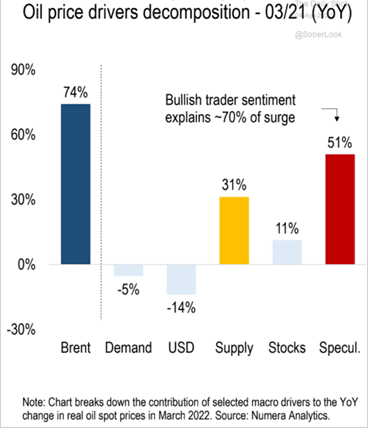

Investors have also found plenty of speculative commodity trades: not only oil and gas but also wheat, sunflower oil, precious and base metals. In the more widely traded markets, speculators constitute a third party able to move prices and, in the cases of oil and wheat, currently seem more influential than the producers themselves or their customers.

Figure 4. It’s a three-party market

Another reflex action has been to sell off European equities without much discrimination, albeit Spanish companies are deemed to be less affected by the invasion. The euro has continued to slide against the generally stronger dollar by more than other major currencies (apart from the yen which the dollar has now usurped as the preferred safe haven). Since the invasion, investors have also been taking their money out of even the safest European sovereign bonds, causing yields to rise sharply by historic standards. Two-year bund yields now seem to be consistently positive for the first time in 8 years.

Nevertheless, a focus for markets much greater than the invasion has been the prospect of aggressive central bank tightening, principally by the Fed but also by many others, including even the ECB. After several false starts last year, the decisive change in the direction of US Treasury yields took place in December and has been accelerating since. Yields have been bumped higher by remarks by Fed officials including even Fed Vice Chair Brainard, who had previously been applauded/pilloried as an arch dove. There is no longer any lingering doubt that the Fed is going both to hike rates and to reduce its balance sheet. The cold reality is that for global investors right now whether the Fed crashes the US economy matters much more than any putative contributory effects from the invasion.

The raised bar for a fabled ‘Fed put’ has, of course, been troubling equity markets since mid-2021, thereby sparking tremendous volatility in the US stock market. This represents the market’s very own regime change and a major challenge in itself, while the invasion is to a large extent only one factor and not even the most important one.

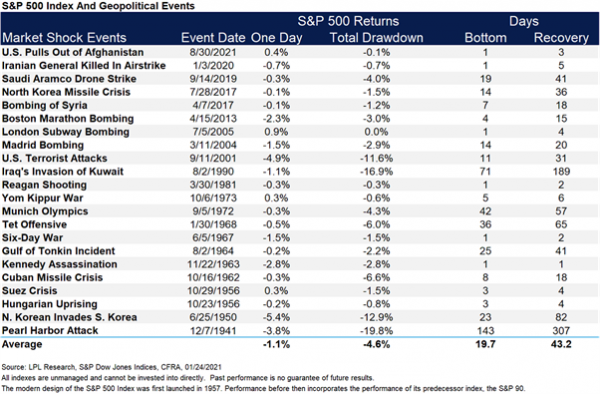

US equity markets have a clear history of shrugging off global crises from Pearl Harbour to the pull-out from Afghanistan last year. Some outcomes are already affecting share prices: such as the damage to the EU economy generally; the proposed surge in defence spending by Germany; the loss of business from closing down operations in Russia; and shortages and potential new sources of energy, food and raw materials as sanctions look like becoming both more stringent and longer lasting.

Figure 4 Crisis? What crisis?

Source: @RyanDetrick

Then there are the wider issues of global stagflation, deglobalisation, protectionism and China risk. There are no easy answers, and Mr Putin is certainly making them more difficult. But many investors are only just beginning to face up to them.